CQC Quality Statements

Theme 3 – How the local authority ensures safety in the system: Safe systems, pathways and transitions

We statement

We work with people and our partners to establish and maintain safe systems of care, in which safety is managed, monitored and assured. We ensure continuity of care, including when people move between services.

What people want

When I move between services, settings or areas, there is a plan for what happens next and who will do what, and all the practical arrangements are in place.

I feel safe and supported to understand and manage any risks.

Please note: In August 2023, the Supreme Court made a judgment in the case of R (Worcestershire County Council) v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care [2023] UKSC 31 which considered which of two local authorities was responsible for providing and paying for “aftercare services” under section 117 of the Mental Health Act. The effect of the judgment is that the law on section 117 and ordinary residence (as set out in the Care and Support Statutory Guidance and below) has not changed, and ordinary residence should be decided by looking at where the person was living immediately before their last detention. Disputes between local authorities regarding ordinary residence disputes will be decided by the Secretary of State in the light of the Supreme Court judgment. See R (on the application of Worcestershire County Council) (Appellant) v Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (Respondent) – The Supreme Court.

July 2024: Section 2, Key Points about Section 117 Aftercare Services has been amended to include reference to the Joint Guidance to Tackle Common Mistakes in Aftercare of Mental Health In-patients published by the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman.

CONTENTS

- 1. Introduction: What is Section 117 Aftercare?

- 2. Key Points about Section 117 Aftercare Services

- 3. Planning Aftercare

- 4. Funding Section 117 Aftercare

- 5. Reviewing and Ending Section 117 Aftercare

- 10. Further Reading

- Appendix 1: Case Law – Ceasing to be Detained and on Leaving Hospital

- Appendix 2: Rules in Relation to CTO Patients in the Community

1. Introduction: What is Section 117 Aftercare?

The Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice (chapter 33) outlines how section 117 of the Act requires Integrated Care Boards (ICBs – formerly known as Clinical Commissioning Groups) and local authorities, working with voluntary agencies, to provide or arrange for the provision of aftercare to patients detained in hospital for treatment under:

- section 3 – detained in hospital for treatment;

- section 37 or 45A – ordered to go to hospital for treatment by a court;

- section 47 or 48 – transferred from prison to hospital under sections of the Act.

This includes patients given leave of absence under section 17 and patients going on community treatment orders (CTOs). It applies to people of all ages, including children and young people.

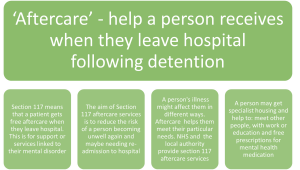

2. Key Points about Section 117 Aftercare Services

(Click on image to enlarge it)

Aftercare services aim to meet a need arising from or related to the patient’s mental disorder and reduce the risk of a deterioration of their mental condition (and, accordingly, reducing the risk of them needing to be readmitted to hospital for treatment). Their aim is to maintain patients in the community, with as few restrictions as necessary, wherever possible.

ICBs and local authorities should interpret the definition of aftercare services broadly. For example, aftercare can include healthcare, social care and employment services, supported accommodation and services to meet the person’s wider social, cultural and spiritual needs – if these services meet a need that arises directly from or is related to their particular mental disorder, and help to reduce the risk of a deterioration in their mental condition.

Aftercare is a vital component in patients’ overall treatment and care. As well as meeting their immediate needs for health and social care, aftercare aims to support them in regaining or enhancing their skills, or learning new skills, to cope with life outside hospital (Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice).

Guidance has been issued by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman and the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman regarding misunderstandings between a local authority and the integrated care board about their collective responsibilities for people receiving Section 117 aftercare services (see Ombudsmen Release Joint Guidance to Tackle Common Mistakes in Aftercare of Mental Health In-patients, LGSCO). The guidance gives case studies highlighting recurring mistakes seen in their joint investigation work. These areas are:

- care planning for patients;

- funding for aftercare;

- accommodation needs;

- ending mental health aftercare.

2.1 Community treatment orders

The duty to provide aftercare services continues as long as the patient is in need of such services. In the case of a patient on a CTO, aftercare must be provided for the whole time they are on the CTO, but this does not mean that their need for aftercare will stop as soon as they are no longer on a CTO.

2.2 Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

See Mental Capacity Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards chapter

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice highlights that safeguards cannot apply to people while they are detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA). The safeguards can, however, apply to a person who has previously been detained in hospital under the MHA.

Therefore, for those who are assessed as eligible for section 117 aftercare funding, and their needs are met in a care home or hospital (for physical treatment), they may be subject to restrictions that deprive them of their liberty. Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) can be used for any patient who is funded for their accommodation, care, and treatment under section 117.

There are some occasions where DoLS can be used together with the MHA, and these are referred to as ‘interfaces’ between the legislations, in which five test cases are applied to help determine eligibility. See Interface between the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the Mental Health Act 1983 (amended 2007) chapter.

2.3 Ordinary residence

See Liverpool City Region Ordinary Residence Practice Guidance chapter

A key consideration when establishing a patient’s eligibility for section 117 aftercare funding is ordinary residence. Section 117(3) of the Act states the ICB, or local Health Board, and the local authority are responsible for funding aftercare in the following circumstances:

- if, immediately before being detained, the person was ordinarily resident in England (for the area in England in which they were ordinarily resident);

- if, immediately before being detained, the person was ordinarily resident in Wales, for the area in Wales in which they ordinarily resident; or

- in any other case for the area in which the person concerned is resident or to which he is sent on discharge by the hospital in which they were detained.

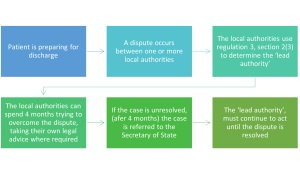

2.3.1 Ordinary residence disputes

The issue of ordinary residence can occur frequently as a reason for disagreement when health and social care services are planning safe discharges. Who Pays? NHS England guidance states that the original ICB remains responsible for the health part of a person’s section 117 aftercare funding once they have been discharged into the community.

The guidance also indicates the definition of ordinary residence must be considered alongside its interpretation under the Care Act 2014, where Regulation 3 must be considered. This includes:

Firstly, determining who the ‘lead authority’ is. The regulations states this is the local authority which:

- is meeting the needs of the adult or carer to whom the dispute relates at the date on which the dispute starts; or

- if no local authority is meeting those needs at that date, is required to do so by regulation 2(3);

If it is unclear who the lead authority is, this is decided by considering section 2 of regulation 3:

- the local authority in whose area the adult needing care is living; or

- if the adult needing care is not living in the area of any local authority, the local authority in whose area that adult is present, must, until the dispute is resolved, carry out the duties under Part 1 of the Act for the adult or carer, as if the adult needing care was ordinarily resident in its area.

The guidance states:

By virtue of regulation 3(7) of the Care and Support (Disputes between Local Authorities) Regulations 2014/2829 disputes must still be referred to the Secretary of State if the local authorities in dispute cannot resolve the dispute within 4 months of the date on which it arose. On receipt of a referral, DHSC will consider, on a case-by-case basis whether the case raises issues similar to the ‘Worcestershire case‘ and, depending on that consideration, how to treat that referral.

2.3.2 Dispute resolution map

(Click on image to enlarge it)

3. Planning Aftercare

The Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice states that although the duty to provide aftercare begins when the patient leaves hospital, the planning of aftercare needs to start as soon as the patient is admitted to hospital. ICBs and local authorities should take reasonable steps, in consultation with the care programme approach (CPA) care co-ordinator and other members of the multi-disciplinary team, to identify appropriate aftercare services for patients in good time for their eventual discharge from hospital or prison.

The duty to provide section 117 aftercare services to a person is triggered by the hospital providing them with care and treatment. If the Responsible Clinician (RC) is considering discharge, they should consider whether the patients aftercare needs have been identified and addressed. This would also apply in cases where the RC is granting extended s17 leave.

If the patient is having either a Hospital Managers Hearing or a Mental Health Tribunal, the ICB and local authority must be notified, as they will be expected to provide information as to what aftercare arrangements could be made available.

Aftercare for all patients admitted to hospital for treatment for mental disorder should be planned within the framework of the CPA. The CPA is an overarching system for coordinating the care of people with mental disorders.

3.1 Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults

The Community Mental Health Framework for Adults and Older Adults sets out that people with mental health problems will be able to:

- access mental health care where and when they need it, and be able to move through the system easily, so that people who need intensive input receive it in the appropriate place, rather than face being discharged to no support;

- manage their condition or move towards their individual recovery on their own terms, surrounded by their families, carers and social networks, and supported in their local community;

- contribute to and be participants in the communities that support them, to whatever extent is comfortable to them.

Every person who requires support, care and treatment in the community should have a co-produced and personalised care plan that considers all of their needs, as well as their rights, under the Care Act and section 117 of the MHA when required.

3.2 Care planning

The level of planning and coordination of care will vary, depending on how complex the person’s needs are. For people with more complex problems, who may require interventions from a number of different professionals, one person should have responsibility for coordinating care and treatment. This coordination role can be provided by workers from different professional backgrounds.

The care plan will include timescales for review, which should be discussed and agreed with the person and those involved in their care from the start. Digital technologies can be used to manage plans, and to allow users to manage their care or record advance choices.

Part of everyone’s role is to work with their community. Local authorities have developed community strengths-based approaches and the core skills of social workers include identifying and connecting people to their social networks and communities. Community connectors / social prescribing link workers must work closely with the all the community services and the local voluntary, community and social enterprise sector. The key functions of this role are to be familiar with the local resources and assets available in the community, vary the support provided, based on needs, and assess a person’s ability and motivation to engage with certain community activities.

The aftercare plan must reflect the needs of the patient and it is important to consider who needs to be involved, in addition to patients themselves. Taking the patient’s views into account, this may include:

- the patient;

- the nearest relative;

- any carer who will be involved in looking after them outside hospital;

- any attorney or deputy;

- an independent mental health advocate;

- an independent mental capacity advocate;

- any other representative nominated by the patient;

- the GP;

- the responsible clinician;

- a psychologist, community mental health nurse and other members of the community team;

- nurses and other professionals involved;

- an employment expert, if employment is an issue;

- a representative of housing authorities;

- in the case of a transferred prisoner, the probation service;

- a representative of any relevant voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise agency;

- a person to who the local authority is considering making direct payments for the patient.

Care planning requires a thorough assessment of the patient’s needs and wishes. It is likely to involve consideration of:

- the patient’s continuing mental healthcare, whether in the community or on an outpatient basis;

- their psychological needs and, where appropriate, their carers;

- their physical healthcare;

- their daytime activities or employment;

- appropriate accommodation;

- their identified risks and safety issues;

- any specific needs arising from, for example co-existing physical disability, sensory impairment, learning disability or autistic spectrum disorder;

- any specific needs arising from drug, alcohol or substance misuse (if relevant);

- any parenting or caring needs;

- social, cultural or spiritual needs;

- counselling and personal support;

- assistance in welfare rights and managing finances;

- involvement of authorities and agencies in a different area, if the patient is not going to live locally;

- the involvement of other agencies, for example the probation service or voluntary organisations (if relevant);

- for a restricted patient, the conditions which the Secretary of State for Justice or the first-tier Tribunal has – or is likely to – impose on their conditional discharge; and

- contingency plans (should the patient’s mental health deteriorate) and crisis contact details.

Professionals with specialist expertise should also be involved in care planning for people with autistic spectrum disorders or learning disabilities.

It is important that those who are involved can take decisions regarding their own involvement and, as far as possible, that of their organisation. If approval for plans needs to be obtained from more senior levels, it is important that this causes no delay to the implementation of the care plan.

If accommodation is to be offered as part of the aftercare plan to patients who are offenders, the circumstances of any victim of the patient’s offence and their families should be taken into account when deciding where the accommodation should be offered. Where the patient is to live may be one of the conditions imposed by the Secretary of State for Justice or the Tribunal when conditionally discharging a restricted patient (see Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice).

4. Funding Section 117 Aftercare

Section 117 aftercare services are free of charge to all relevant persons. The amount awarded by the local authority must be the amount it costs the local authority to meet the person’s needs. In establishing the ‘cost to the local authority’, consideration should be given to local market intelligence and costs of relevant local quality care and support provision to ensure that the personal budget reflects local market conditions and that appropriate care that meets needs can be obtained for the amount specified (see Personal Budgets chapter).

If, at any point, it becomes clear that a person who is be eligible for section 117 aftercare has been paying for services, they can reclaim these payments as long as clear evidence is provided of their detention in hospital or prison.

Direct payments can be made in respect of aftercare to the patient or, where the patient is a child or a person who lacks capacity, to a representative who consents to the making of direct payments in respect of the patient (see Direct Payments chapter). A payment can only be made if valid consent has been given. In determining whether a direct payment should be made, funding authorities must have regard to whether it is appropriate for a person with that person’s condition, taking into account the impact of that condition on the person’s life and whether a direct payment represents value for money. A payment can also, in certain circumstances, be made to a nominated person.

The relevant social services authority for the funding of section 117 is usually that where the person was ordinarily resident prior to their first detention on a qualifying section for s117, unless that local authority with the relevant ICB with good reason ended the s117 entitlement.

It is the responsibility of the local authority to hold a register of all those subject to section 117 within the authority. The local authority and ICB should maintain a record of whom they provide aftercare services for in their area and out of county.

5. Reviewing and Ending Section 117 Aftercare

Aftercare lasts as long as there is a need to be met and must remain in place until such a time that both the ICB and the local authority are satisfied that the patient no longer has needs for aftercare services. Care and treatment needs can be reviewed periodically by the ICB and the local authority, and aftercare can be altered as the person’s needs change.

Section 117 aftercare cannot be withdrawn without reassessing the person’s needs. The person must be fully involved in any decision-making process in relation to the ending of aftercare, including, if appropriate consultation with relevant carer/s and advocate/s.

Aftercare cannot be withdrawn simply because someone has been discharged from specialist mental health services, or an certain period has passed, or they have been returned to hospital and / or further detained under MHA and / or Mental Capacity Act (MCA).

If aftercare services area withdrawn, they can be reinstated if it becomes obvious that withdrawing the services was premature or unlawful.

The patient is entitled to refuse aftercare services and cannot be forced to accept them. It is important to note that just because someone may refuse services, this does not automatically mean that there is not a need, and therefore does not automatically mean that aftercare services should be withdrawn.

It may well be that whilst receiving s117 aftercare for a mental disorder, a person requires services for a separate physical or mental disorder, care for these would need to be addressed by a separate care plan under the Care Act.

10. Further Reading

10.1 Relevant chapter

6.2 Relevant information

Discharge from Mental Health Inpatient Settings (DHSC)

Transition between inpatient mental health and community and care home settings (NICE)

Appendix 1: Case Law – Ceasing to be Detained and on Leaving Hospital

In R (on the application of CXF (by his mother, his litigation friend)) v Central Bedfordshire Council [2018] EWCA Civ 2852, the Court considered whether:

- the public body’s duty to provide after-care services to a detained patient extended to the funding of cost of visits of patient’s mother.

- Whether mother’s expenses could be recovered as provision of after-care services.

- Whether patient had left hospital and ceased to be detained on escorted day trips.

The facts

- The claimant had been diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder, severe and profound learning disabilities, speech and language impairment and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

- From June 2016 he had been detained as a patient for purposes of treatment under section 3 of the MHA 1983. Because of the limited number of specialist residential placements at which suitable treatment could be provided, he was detained at an institution in Norfolk some 120 miles from his parental home in Bedfordshire.

- Under section 17 MHA 1983 his clinician granted him a daily leave of absence to go on bus trips which could take place up to three times a day. Once a week his mother would make the 240 mile round trip to visit him and would go with him on some of these bus trips and help engage in other activities such as shopping, walks on beaches and visits to favourite museums.

- It was accepted by the court that these visits by the mother and the contact with her were therapeutically beneficial to him.

- The claimant argued that the expenses should be reimbursed under section 117 MHA 1983 which imposed a duty to provide ‘aftercare’ services to persons who were detained under the MHA and then ‘cease to be detained and … leave hospital.’

Decision

- The judge at first instance rejected the claim taking the view that neither the local authority nor the CCG were required to meet the mother’s travelling expenses. The judge considered that it was clear that the claimant remained at all times detained under the Act and had not left hospital even when he was enjoying a leave of absence under s 17.

- The appeal was dismissed and It was held:

- The claimant was still ‘detained’ in hospital for the purposes of s 117 MHA 1983 despite the grant of temporary leave of absence from time to time under s 17 MHA 1983.

- It was not, in the court’s view, realistic to suggest that the claimant had left hospital within the terms of s117 MHA 1983. The purpose of s117 was to arrange for the provision of services to a person who had been but was not currently being provided with treatment as a hospital patient.

- That purpose was only capable of being fulfilled if the person was not currently admitted to a hospital at which they were receiving treatment, which was not the case here.

- It was not necessary for the patient to have been discharged for the section to apply. Each return for a supervised trip did not amount to a readmission. The trips were part of the hospital treatment and did not constitute aftercare services to which the section applied.

- The claimant had not left hospital in the meaning of the section on these escorted day trips. Therefore, no expenses could be claimed under section 117 of MHA

Appendix 2: Rules in Relation to CTO Patients in the Community

There are two requirements for CTO patients in the community to be given medication for mental disorder. These are:

- the usual authority: what would be required to give a patient medication if they were not subject to the MHA, that is:

- the patient’s consent if the patient has capacity; or

- in the patient’s best interest if the patient lacks capacity, but only if the patient does not resist or it is given with the authority of a person with a lasting power of attorney for health and welfare decisions

- a certificate: the Part 4A certificate is signed by the Responsible Clinician (or Approved Clinician with responsibility for medication) if the patient has capacity and is consenting; the certificate is signed by a SOAD (Second opinion appointed doctor) if the patient lacks capacity.

CTO patients require a certificate.

The Supreme Court has held in Welsh Ministers v PJ [2018] UKSC 66 that there is no power to impose conditions on a CTO which has the effect of depriving a patient of his liberty. Hence if a person is subject to a CTO and a deprivation of liberty (DOL) the Court of Protection needs to authorise the DOL.