Theme 3 – How the local authority ensures safety in the system: Safeguarding

We statement

We work with people to understand what being safe means to them as well as our partners on the best way to achieve this. We concentrate on improving people’s lives while protecting their right to live in safety, free from bullying harassment, abuse, discrimination, avoidable harm and neglect. We make sure we share concerns quickly and appropriately.

What people expect

I feel safe and supported to understand and manage any risks.

1. The Local Authority’s Role in carrying out Enquiries

Local authorities must make enquiries, or cause others to do so, if they reasonably suspect an adult is at risk of, being abused or neglected (see Adult Safeguarding).

An enquiry is the action taken or instigated by the local authority in response to a concern that abuse or neglect may be taking place.

An enquiry could range from a conversation with the adult, or if they lack capacity, or have substantial difficulty in understanding the enquiry, their representative or advocate, prior to initiating a formal enquiry under section 42, right through to a much more formal multi-agency plan or course of action.

Whatever the course of subsequent action, the professional concerned should record:

- the concern;

- the adult’s views, wishes;

- any immediate action taken; and

- the reasons for those actions.

The purpose of the enquiry is to decide whether or not the local authority or another organisation, or person, should do something to help and protect the adult. If the local authority decides that another organisation should make the enquiry, for example a care provider, the local authority should be clear about:

- timescales;

- the outcomes of the enquiry;

- what action will follow if this is not done.

What happens as a result of an enquiry should reflect the adult‘s wishes wherever possible. If they lack capacity it should be in their best interests if they are not able to make the decision, and be proportionate to the level of concern.

The adult should always be involved from the beginning of the enquiry unless there are exceptional circumstances that would increase the risk of abuse. If the adult has substantial difficulty in being involved, and where there is no one appropriate to support them, then the local authority must arrange for an independent advocate to represent them for the purpose of facilitating their involvement (see Independent Advocacy).

Professionals and other staff need to handle enquiries in a sensitive and skilled way to ensure distress to the adult is minimised. It is likely that many enquiries will require the input and supervision of a social worker, particularly the more complex situations and to support the adult to realise the outcomes they want and to reach a resolution or recovery. For example, where abuse or neglect is suspected within a family or informal relationship it is likely that a social worker will be the most appropriate lead. Personal and family relationships within community settings can prove both difficult and complex to assess and intervene in. The dynamics of personal relationships can be extremely difficult to judge and re-balance. For example, an adult may make a choice to be in a relationship that causes them emotional distress which outweighs, for them, the unhappiness of not maintaining the relationship.

Whilst work with the adult may frequently require the input of a social worker, other aspects of enquiries may be best undertaken by others with appropriate skills and knowledge. For example, health professionals should undertake enquiries and treatment plans relating to medicines management or pressure sores.

2. Criminal Offences and Adult Safeguarding

Everyone is entitled to the protection of the law and access to justice. Although the local authority has the lead role in making enquiries, where criminal activity is suspected, the early involvement of the police is likely to have benefits in many cases.

Behaviour which amounts to abuse and neglect also often constitutes specific criminal offences, for example:

- physical or sexual assault or rape;

- psychological abuse or hate crime;

- wilful neglect;

- unlawful imprisonment;

- theft and fraud;

- certain forms of discrimination of legislation.

For the purpose of court proceedings, a witness is competent if they can understand the questions and respond in a way that the court can understand. Police have a duty under legislation to assist those witnesses who are vulnerable and intimidated.

A range of special measures are available to facilitate the gathering and giving of evidence by vulnerable and intimidated witnesses. Consideration of specials measures should occur from the onset of a police investigation. In particular:

- immediate referral or consultation with the police will enable the police to establish whether a criminal act has been committed and this will give an opportunity of determining if, and at what stage, the police need to become involved further and undertake a criminal investigation;

- the police have powers to take specific protective actions, such as Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPO);

- a higher standard of proof is required in criminal proceedings (‘beyond reasonable doubt’) than in disciplinary or regulatory proceedings (where the test is the balance of probabilities) and so early contact with police may assist in obtaining and securing evidence and witness statements;

- early involvement of the police will help ensure that forensic evidence is not lost or contaminated;

- police officers need to have considerable skill in investigating and interviewing adults with a range of disabilities and communication needs if early involvement is to prevent the adult being interviewed unnecessarily on subsequent occasions. Research has found that sometimes evidence from victims and witnesses with learning disabilities is discounted. This may also be true of others such as people with dementia. It is crucial that reasonable adjustments are made and appropriate support given, so people can get equal access to justice;

- police investigations should be coordinated with health and social care enquiries but they may take priority, however the local authority’s duty to ensure the wellbeing and safety of the person continues;

- guidance should include reference to support relating to criminal justice matters which is available locally from such organisations as Victim Support and court preparation schemes;

- some witnesses will need protection;

- the police may be able to get victim support in place.

Special Measures were introduced through legislation in the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 and include a range of measures to support witnesses to give their best evidence and to help reduce some of the anxiety when attending court. Measures in place include the use of screens around the witness box, the use of live link or recorded evidence in chief and the use of an intermediary to help witnesses understand the questions they are being asked and to give their answers accurately.

Vulnerable adult witnesses have one of the following:

- mental disorder;

- learning disability;

- physical disability.

These witnesses are only eligible for special measures if the quality of evidence that is given by them is likely to be diminished by reason of the disorder or disability.

Intimidated witnesses are defined as those whose quality of evidence is likely to be diminished by reason of fear or distress. In determining whether a witness falls into this category the court takes account of:

- the nature and alleged circumstances of the offence;

- the age of the witness;

- the social and cultural background and ethnic origins of the witness;

- the domestic and employment circumstances of the witness;

- any religious beliefs or political opinions of the witness;

- any behaviour towards the witness by the accused or third party.

Also falling into this category are:

- complainants in cases of sexual assault;

- witnesses to specified gun and knife offences;

- victims of and witnesses to domestic abuse, racially motivated crime, crime motivated by reasons relating to religion, homophobic crime, gang related violence and repeat victimisation;

- those who are older and frail;

- the families of homicide victims.

Registered Intermediaries (RIs) facilitate communication with vulnerable witnesses in the criminal justice system.

A criminal investigation by the police takes priority over all other enquiries. Although a multi-agency approach should be agreed to ensure that the interests and personal wishes of the adult will be considered throughout, even if they do not wish to provide any evidence or support a prosecution. The welfare of the adult and others, including children, is paramount and requires continued risk assessment to ensure the outcome is in their interests and enhances their wellbeing.

If the adult has the mental capacity to make informed decisions about their safety and they do not want any action to be taken, this does not preclude the sharing of information with relevant professional colleagues. This enables professionals to assess the risk of harm and be confident that the adult is not being unduly influenced, coerced or intimidated and is aware of all the options. This will also enable professionals to check the safety and validity of decisions made. It is good practice to inform the adult that this action is being taken unless doing so would increase the risk of harm.

3. The Mental Capacity Act 2005

See also Mental Capacity.

People must be assumed to have capacity to make their own decisions and be given all practicable help before anyone treats them as not being able to make their own decisions. Where an adult is found to lack capacity to make a decision then any action taken, or any decision made for, or on their behalf, must be made in their best interests.

Professionals and other staff need to understand and always work in line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA). They should use their professional judgement to balance competing views. They will need considerable guidance and support from their employers if they are to help adults manage risk in ways and put them in control of decision making if possible.

Regular face to face supervision from skilled managers is essential to enable staff to work confidently and competently in difficult and sensitive situations.

Mental capacity is frequently raised in relation to adult safeguarding. The requirement to apply the MCA in adult safeguarding enquiries (see Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice, Office of the Public Guardian) challenges many professionals and requires utmost care, particularly where it appears an adult has capacity for making specific decisions that nevertheless places them at risk of being abused or neglected.

3.1 Ill treatment and wilful neglect

See also Ill Treatment and Wilful (Deliberate) Neglect chapter

The MCA created the criminal offences of ill treatment and wilful neglect in respect of people who lack the ability to make decisions. The offences can be committed by anyone responsible for that adult’s care and support – paid staff, but also family carers as well as people who have the legal authority to act on that adult’s behalf (that is persons with power of attorney or Court appointed deputies).

These offences are punishable by fines and / or imprisonment.

Ill treatment covers both deliberate acts of ill treatment and also those acts which are reckless which results in ill treatment.

Wilful neglect requires a serious departure from the required standards of treatment and usually means that a person has deliberately failed to carry out an act that they knew they were under a duty to perform.

3.2 Attorneys and deputies

If someone has concerns about the actions of an attorney acting under a registered enduring power of attorney (EPA) or lasting power of attorney (LPA), or a deputy appointed by the Court of Protection, they should contact the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG). The OPG can investigate the actions of a deputy or attorney and can also refer concerns to other relevant agencies.

When it makes a referral, the OPG will make sure that the relevant agency keeps it informed of the action it takes. The OPG can also make an application to the Court of Protection if it needs to take possible action against the attorney or deputy.

Whilst the OPG primarily investigates financial abuse, it is important to note that that it also has a duty to investigate concerns about the actions of an attorney acting under a health and welfare lasting power of attorney or a personal welfare deputy. The OPG can investigate concerns about an attorney acting under a registered enduring power of attorney or lasting power of attorney, regardless of the adult’s capacity to make decisions. Read about the role and powers of the OPG and its policy in relation to adult safeguarding.

4. Information Gathering

If the issue cannot be resolved through these means or the adult remains at risk of abuse or neglect (real or suspected) then the local authority’s enquiry duty under section 42 continues until it decides what action is necessary to protect the adult and by whom and ensures itself that this action has been taken.

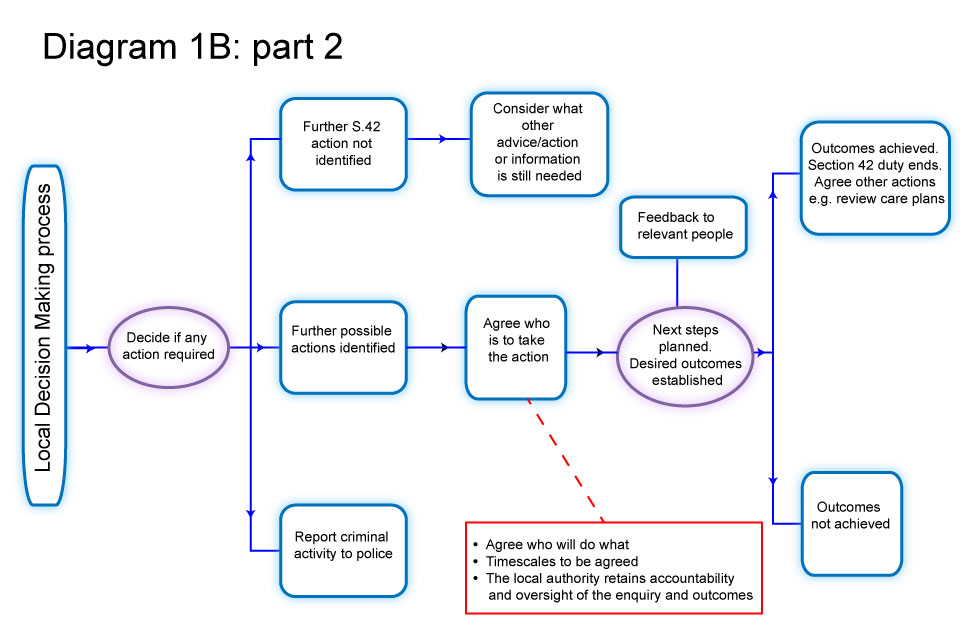

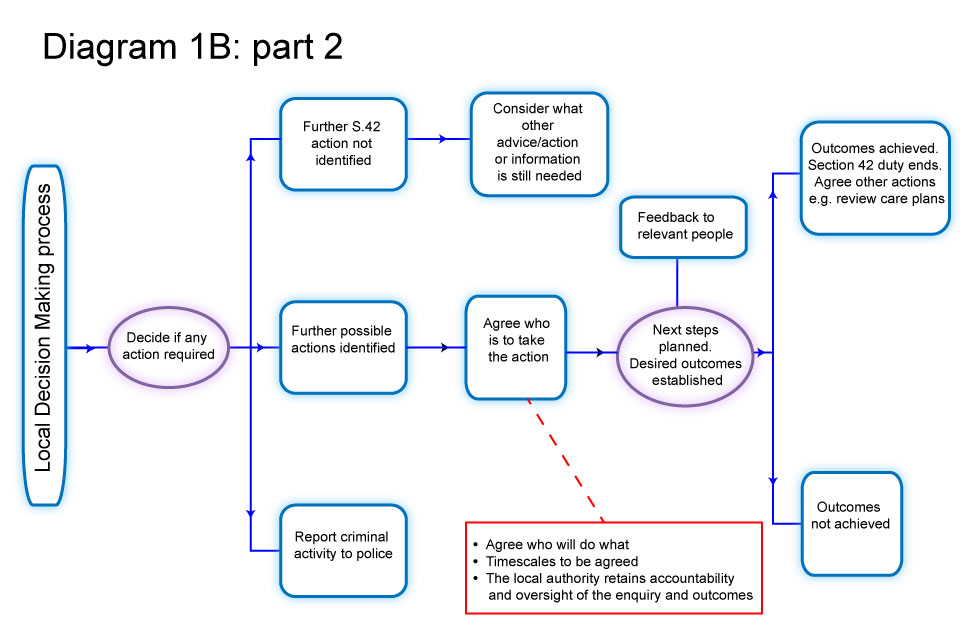

Principles for local decision making process:

- empowerment: presumption of person led decisions and informed consent;

- prevention: it is better to take action before harm occurs;

- proportionate and least intrusive response appropriate to the risk presented;

- protection: support and representation for those in greatest need;

- partnership: local solutions through services working with their communities;

- communities: have a part to play in preventing, detecting and reporting neglect and abuse;

- accountability and transparency in delivering safeguarding;

- feeding back whenever possible.

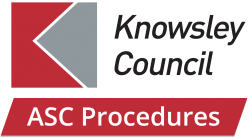

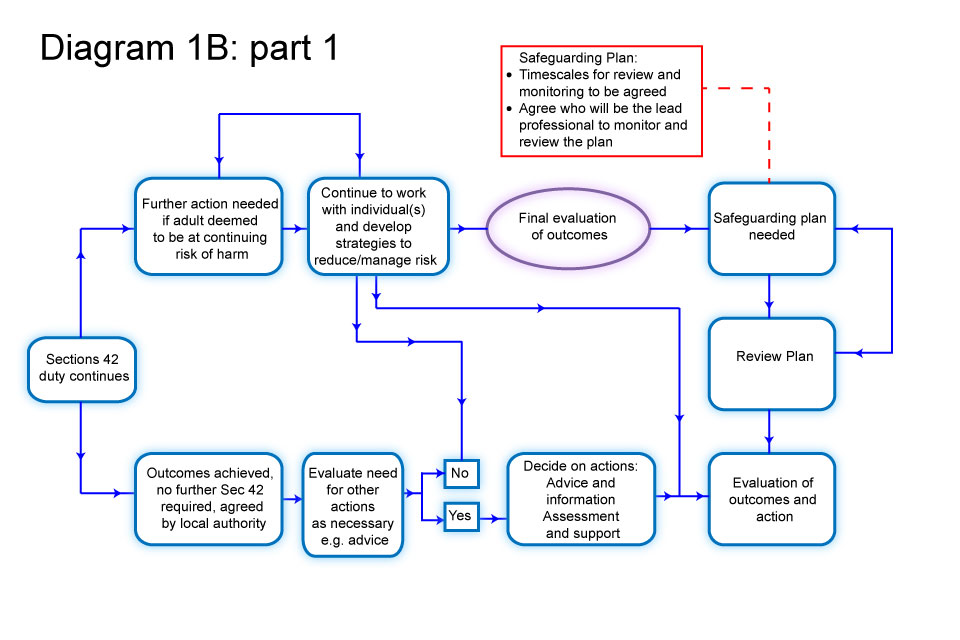

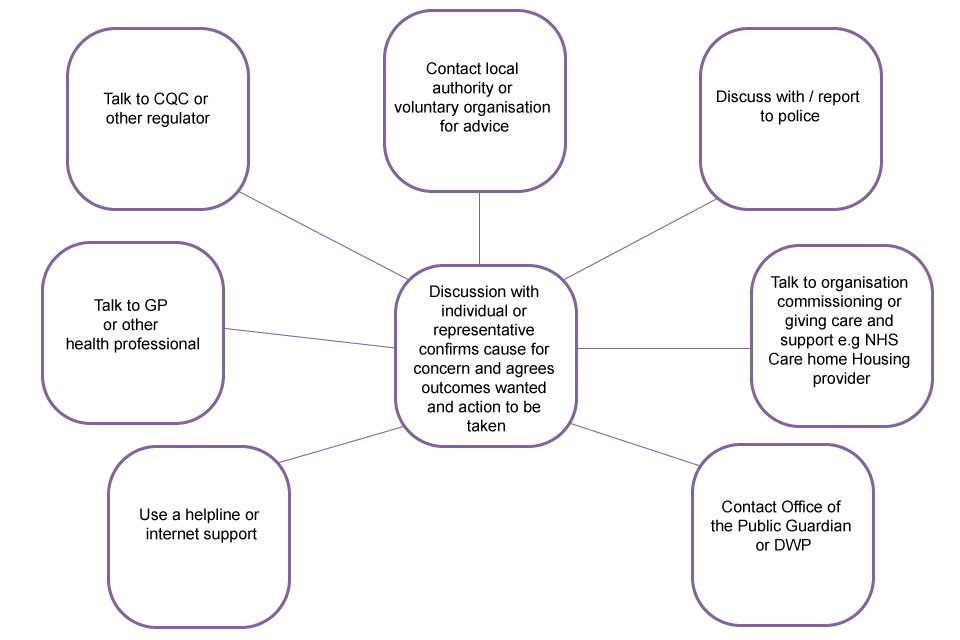

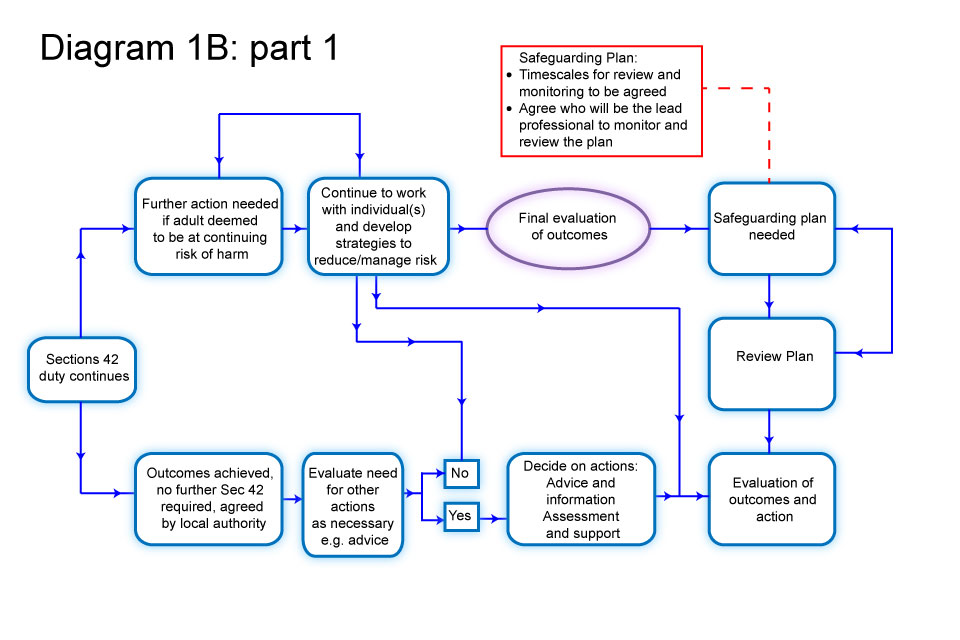

Decision making diagrams

5. When should an Enquiry take place?

Local authorities must make enquiries, or cause another agency to do so, whenever abuse or neglect are suspected in relation to an adult and the local authority thinks it necessary to enable it to decide what (if any) action is needed to help and protect the adult.

The scope of that enquiry, who leads it and its nature, and how long it takes, will depend on the particular circumstances.

It will usually start with asking the adult their view and wishes which will often determine what next steps to take.

Everyone involved in an enquiry must focus on improving the adult’s wellbeing and work together to that shared aim.

At this stage, the local authority also has a duty to consider whether the adult requires an independent advocate to represent and support the adult in the enquiry.

See Decision Making diagrams above, which highlight appropriate pauses for reflection, consideration and professional judgement and reflect the different routes and actions that might be taken.

6. Objectives of an Enquiry

The objectives of an enquiry into abuse or neglect are to:

- establish facts;

- ascertain the adult’s views and wishes;

- assess the needs of the adult for protection, support and redress and how they might be met;

- protect from the abuse and neglect, in accordance with the wishes of the adult;

- make decisions as to what follow up action should be taken with regard to the person or organisation responsible for the abuse or neglect;

- enable the adult to achieve resolution and recovery.

The first priority should always be to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the adult.

The adult should experience the safeguarding process as empowering and supportive. Practitioners should wherever practicable seek the consent of the adult before taking action. However, there may be circumstances when consent cannot be obtained because the adult lacks the capacity to give it, but it is in their best interests to undertake an enquiry.

Whether or not the adult has capacity to give consent, action may need to be taken if others are or will be put at risk if nothing is done or where it is in the public interest to take action because a criminal offence has occurred.

It is the responsibility of all staff and members of the public to act on any suspicion or evidence of abuse or neglect and to pass on their concerns to a responsible person or agency.

From BMA adult safeguarding toolkit:

…where a competent adult explicitly refuses any supporting intervention, this should normally be respected. Exceptions to this may be where a criminal offence may have taken place or where there may be a significant risk of harm to a third party. If, for example, there may be an abusive adult in a position of authority in relation to other vulnerable adults [sic], it may be appropriate to breach confidentiality and disclose information to an appropriate authority. Where a criminal offence is suspected it may also be necessary to take legal advice. Ongoing support should also be offered. Because an adult initially refuses the offer of assistance he or she should not therefore be lost to or abandoned by relevant services. The situation should be monitored and the individual informed that she or he can take up the offer of assistance at any time.

7. What should an Enquiry take into Account?

The wishes of the adult are very important, particularly where they have capacity to make decisions about their safeguarding. The wishes of those that lack capacity are of equal importance. Wishes need to be balanced alongside wider considerations such as the level of risk or risk to others including any children affected. All adults at risk, regardless of whether they have capacity or not may want highly intrusive help, such as the barring of a person from their home, or a person to be brought to justice or they may wish to be helped in less intrusive ways, such as through the provision of advice as to the various options available to them and the risks and advantages of these various options.

Where an adult lacks capacity to make decisions about their safeguarding plans, then a range of options should be identified, which help the adult stay as much in control of their life as possible (see Mental Capacity). Wherever possible, the adult should be supported to recognise risks and to manage them. Safeguarding plans should empower the adult as far as possible to make choices and to develop their own capability to respond to them.

Any intervention in family or personal relationships needs to be carefully considered. While abusive relationships never contribute to the wellbeing of an adult, interventions which remove all contact with family members may also be experienced as abusive interventions and risk breaching the adult’s right to family life if not justified or proportionate. Safeguarding needs to recognise that the right to safety needs to be balanced with other rights, such as rights to liberty and autonomy, and rights to family life. Action might be primarily supportive or therapeutic, or it might involve the application of civil orders, sanctions, suspension, regulatory activity or criminal prosecution, disciplinary action or deregistration from a professional body.

It is important, when considering the management of any intervention or enquiry, to approach reports of incidents or allegations with an open mind. In considering how to respond the following factors need to be considered:

- the adult’s needs for care and support;

- the adult’s risk of abuse or neglect;

- the adult’s ability to protect themselves or the ability of their networks to increase the support they offer;

- the impact on the adult, their wishes;

- the possible impact on important relationships;

- potential of action and increasing risk to the adult;

- the risk of repeated or increasingly serious acts involving children, or another adult at risk of abuse or neglect;

- the responsibility of the person or organisation that has caused the abuse or neglect;

- research evidence to support any intervention.

8. Who can carry out an Enquiry?

Although the local authority is the lead agency for making enquiries, it may require others to undertake them. The specific circumstances will often determine who the right person is to begin an enquiry. In many cases a professional who already knows the adult will be the best person. They may be a social worker, a housing support worker, a GP or other health worker such as a community nurse. The local authority retains the responsibility for ensuring that the enquiry is referred to the right place and is acted upon.

The local authority, in its lead and coordinating role, should assure itself that the enquiry satisfies its duty under section 42 to decide:

- what action (if any) is necessary to help and protect the adult;

- by whom;

- to ensure that such action is taken when necessary.

The local authority is able to challenge the body making the enquiry if it considers that the process and / or outcome is unsatisfactory.

8.1 Police

Where a crime is suspected and referred to the police, the police must lead the criminal investigations, with the local authority’s support where appropriate, for example by providing information and assistance. The local authority has an ongoing duty to promote the wellbeing of the adult in these circumstances by assessing, offering or organising care and support to ensure the wellbeing of the person by meeting their needs and ensuring their safety.

8.2 Employers

Employers must ensure that staff, including volunteers, are trained in recognising the signs or symptoms of abuse or neglect, how to respond and where to go for advice and assistance. These are best written down in shared policy documents that can be easily understood and used by all the key organisations.

Employers must also ensure all staff keep accurate records, stating what the facts are and what are the known opinions of professionals and others and differentiating between fact and opinion. It is vital that the views of the adult are sought and recorded. These should include the outcomes that the adult wants, such as feeling safe at home, access to community facilities, restricted or no contact with certain individuals or pursuing the matter through the criminal justice system.

9. What happens after an Enquiry?

Once the wishes of the adult have been ascertained and an initial enquiry undertaken, discussions should be undertaken with them as to whether further enquiry is needed and what further action could be taken.

That action could take a number of courses including:

- disciplinary action;

- complaints;

- criminal investigations; or

- work by contracts managers and CQC to improve care standards.

Those discussions should enable the adult to understand what their options might be and how their wishes might best be realised. Social workers must be able to set out both the civil and criminal justice approaches that are open and other approaches that might help to promote their wellbeing, such as therapeutic or family work, mediation and conflict resolution, peer or circles of support. In complex domestic circumstances, it may take the adult some time to gain the confidence and self-esteem to protect themselves and take action and their wishes may change. The police, health service and others may need to be involved to help ensure these wishes are realised.

10. Safeguarding Plans

Once the facts have been established, a further discussion of the needs and wishes of the adult is likely to take place. This could be focused safeguarding planning to enable the adult to achieve resolution or recovery, or fuller assessments by health and social care agencies (for example a needs assessment under the Care Act). This will entail joint discussion, decision taking and planning with the adult for their future safety and wellbeing. This applies if it is concluded that the allegation is true or otherwise, as many enquiries may be inconclusive.

The local authority must determine what further action is necessary. Where the local authority determines that it should itself take further action (for example, a protection plan), then the authority would be under a duty to do so.

The MCA is clear that local authorities must presume that an adult has the capacity to make a decision until there is a reason to suspect that capacity is in some way compromised; the adult is best placed to make choices about their wellbeing which may involve taking certain risks. Where the adult may lack capacity to make decisions about arrangements for enquiries or managing any abusive situation, their capacity must be assessed and any decision made in their best interests.

If the adult has the capacity to make decisions in this area of their life and declines assistance, this may limit the safeguarding intervention that organisations can make. The focus should then be on harm reduction. It should not however limit the action that may be required by the local authority to protect others who are at risk of harm. The potential for ‘undue influence’ will need to be considered if relevant. If the adult is thought to be refusing intervention on the grounds of duress then action must be taken.

In order to make sound decisions, the adult’s emotional, physical, intellectual and mental capacity in relation to self-determination and consent and any intimidation, misuse of authority or undue influence will have to be assessed. Read the guidance on the Mental Capacity Act: Making Decisions (Office of the Public Guardian, 2014) for information.

11. Taking Action

Once enquiries are completed, the outcome should be notified to the local authority which should then determine with the adult what, if any, further action is necessary and acceptable. It is for the local authority to determine the appropriateness of the outcome of the enquiry. One outcome of the enquiry may be the formulation of agreed action for the adult which should be recorded on their care plan. This will be the responsibility of the relevant agencies to implement.

In relation to the adult, this should set out:

- what steps are to be taken to assure their safety in future in relation to identified risks;

- the provision of any support, treatment or therapy including ongoing advocacy;

- any modifications needed in the way services are provided (for example same gender care or placement; appointment of an Office of the Public Guardian deputy);

- how best to support the adult through any action they take to seek justice or redress;

- any ongoing risk management strategy as appropriate;

- any action to be taken in relation to the person or organisation that has caused the concern.

12. Person Alleged to be Responsible for Abuse or Neglect

When a complaint or allegation has been made against a member of staff, including people employed by the adult, they should be made aware of their rights under employment legislation and any internal disciplinary procedures.

If a person who is alleged to have carried out the abuse themselves has care and support needs and is unable to understand the significance of questions put to them or their replies, they should be assured of their right to the support of an ‘appropriate’ adult if they are questioned in relation to a suspected crime by the police under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE). Victims of crime and witnesses may also require the support of an ‘appropriate’ adult.

Under the MCA, people who lack capacity and are alleged to be responsible for abuse, are entitled to the help of an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate, to support and represent them in the enquiries that are taking place (see Independent Mental Capacity Advocate Service). This is separate from the decision whether or not to provide the victim of abuse with an independent advocate under the Care Act.

The Police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) should agree procedures with the local authority, care providers, housing providers, and the NHS / Integrated Care Board (ICB) to cover the following situations:

- action pending the outcome of the police and the employer’s investigations;

- action following a decision to prosecute an individual;

- action following a decision not to prosecute;

- action pending trial;

- responses to both acquittal and conviction.

Employers who are also providers or commissioners of care and support have a duty to the adult and a responsibility to take action in relation to the employee when allegations of abuse are made against them. Employers should ensure that their disciplinary procedures are compatible with the responsibility to protect adults at risk of abuse or neglect.

With regard to abuse, neglect and misconduct within a professional relationship, codes of professional conduct and /or employment contracts should be followed and should determine the action that can be taken. Robust employment practices, with checkable references and recent disclosure and barring checks are important (see Disclosure and Barring Service). Reports of abuse, neglect and misconduct should be investigated and evidence collected.

Where appropriate, employers should report workers to the statutory and other bodies responsible for professional regulation such as the General Medical Council and the Nursing and Midwifery Council. If someone is removed from their role providing regulated activity following a safeguarding incident the regulated activity provider (or if the person has been provided by an agency or personnel supplier, the legal duty sits with them) has a legal duty to refer to the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS). The legal duty to refer to the DBS also applies where a person leaves their role to avoid a disciplinary hearing following a safeguarding incident and the employer / volunteer organisation feels they would have dismissed the person based on the information they hold.

The standard of proof for prosecution is ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. The standard of proof for internal disciplinary procedures and for discretionary barring consideration by the DBS and the Vetting and Barring Board is usually the civil standard of ‘on the balance of probabilities’. This means that when criminal procedures are concluded without action being taken this does not automatically mean that regulatory or disciplinary procedures should cease or not be considered. In any event there is a legal duty to make a safeguarding referral to DBS if a person is dismissed or removed from their role due to harm to a child or a vulnerable adult.

13. Allegations against People in Positions of Trust

See also North West Policy for Managing Concerns around People in Positions of Trust with Adults who have Care and Support Needs

The local authority’s relevant partners and those providing universal care and support services, should have clear policies in line with those from the Safeguarding Adults Board for dealing with allegations against people who work, in either a paid or unpaid capacity, with adults with care and support needs. Such policies should make a clear distinction between an allegation, a concern about the quality of care or practice or a complaint.

Safeguarding adults boards need to establish and agree a framework and process for how allegations against people working with adults with care and support needs (that is those in positions of trust) should be notified and responded to. Whilst the focus of safeguarding adults work is to safeguard one or more identified adults with care and support needs, there are occasions when incidents are reported that do not involve an adult at risk, but indicate, nevertheless, that a risk may be posed to adults at risk by a person in a position of trust.

Where such concerns are raised about someone who works with adults with care and support needs, it will be necessary for the employer (or student body or voluntary organisation) to assess any potential risk to adults with care and support needs who use their services, and, if necessary, to take action to safeguard those adults.

Examples of such concerns could include allegations that relate to a person who works with adults with care and support needs who has:

- behaved in a way that has harmed, or may have harmed an adult or child;

- possibly committed a criminal offence against, or related to, an adult or child;

- behaved towards an adult or child in a way that indicates they may pose a risk of harm to adults with care and support needs.

When a person’s conduct towards an adult may impact on their suitability to work with or continue to work with children, this must be referred to the local authority’s designated officer.

If a local authority is given information about such concerns they should give careful consideration to what information should be shared with employers (or student body or voluntary organisation) to enable risk assessment.

Employers, student bodies and voluntary organisations should have clear procedures in place setting out the process, including timescales, for investigation and what support and advice will be available to individuals against whom allegations have been made. Any allegation against people who work with adults should be reported immediately to a senior manager within the organisation. Employers, student bodies and voluntary organisations should have their own sources of advice (including legal advice) in place for dealing with such concerns.

If an organisation removes an individual (paid worker or unpaid volunteer) from work with an adult with care and support needs (or would have, had the person not left first) because the person poses a risk of harm to adults, the organisation must make a referral to the DBS. It is an offence to fail to make a referral without good reason.

Allegations against people who work with adults at risk must not be dealt with in isolation. Any corresponding action necessary to address the welfare of adults with care and support needs should be taken without delay and in a coordinated manner, to prevent the need for further safeguarding in future.

Local authorities should ensure that their safeguarding information and advice services are clear about the responsibilities of employers, student bodies and voluntary organisations, in such cases, and signpost them to their own procedures and legal advice appropriately. Information and advice services should also be equipped to advise on appropriate information sharing and the duty to cooperate (see Information and Advice chapter).

Local authorities should ensure that there are appropriate arrangements in place to effectively liaise with the police and other agencies to monitor the progress of cases and ensure that they are dealt with as quickly as possible, consistent with a thorough and fair process.

Decisions on sharing information must be justifiable and proportionate, based on the potential or actual harm to adults or children at risk and the rationale for decision making should always be recorded.

When sharing information about adults, children and young people at risk between agencies it should only be shared:

- where relevant and necessary, not simply all the information held;

- with the relevant people who need all or some of the information;

- when there is a specific need for the information to be shared at that time.

14. Further Reading

14.1 Relevant chapters

Adult Safeguarding

Information Sharing and Confidentiality

14.2 Relevant information

Chapter 14, Safeguarding, Care and Support Statutory Guidance (Department of Health and Social Care)

Making Decisions on the Duty to carry out Safeguarding Adults Enquiries: Resources (LGA)

Gaining Access to an Adult Suspected to be at Risk of Neglect or Abuse (SCIE)

Thanks for your feedback!